6. Strategic or city shaping infrastructure

The accessibility effects of strategic transport initiatives can change a city’s development patterns and growth trajectory. This can change the decisions people and businesses make about where to locate, setting a new geography of land values. The market then signals where new and/or intensified urban development is warranted, creating a shift in urban form and, sometimes, structure.

A shift in urban form could include higher density residential, mixed use or commercial development around a railway station in response to an increase in accessibility. For example, the density of development in Chatswood (Sydney) has significantly shifted with an increase in density associated with the completion of the Epping to Chatswood rail line and associated redevelopment of the railway station. Precinct planning is generally undertaken to identify where an intensification of urban development is warranted. The Sydenham to Bankstown Urban Renewal Corridor Strategy identifies opportunities where the density of development can be accommodated through rezoning precincts that are expected to experience increased accessibility associated with the Sydney Metro City and South West project. This project is discussed in more detail below.

In terms of a shift in urban structure, this is likely to occur more gradually as travel patterns shift and may result in the identification of new centres for growth or the elevation of the role of existing centres. For example, the proposed second airport at Badgerys Creek in south west Sydney provides an opportunity to reshape the urban structure of Sydney, particularly outer Western Sydney if adequate connections are provided between the airport and major centres such as Parramatta. This will significantly shift travel patterns and increase accessibility to employment for residents in western Sydney and further support the role of Parramatta as Sydney’s second CBD. The need for strong coordination to achieve this is discussed in more detail below.

These processes are understood intuitively by people as they see and experience - for example - the nexus between highway development and increasing land values and housing development in peri-urban regions.

Clearly, strategic transport investments can be a powerful policy lever for determining a city’s structure, with land use regulation playing a supplementary role in managing urban development. This means that strategic transport initiatives need to be conceptualised within the context of a preferred urban structure rather than a traditional approach where transport investment simply responds to demonstrated demand.

In some instances, it may make more economic sense to prioritise strategic transport infrastructure that will reshape the city in permanently advantageous ways over initiatives that solve evident congestion problems.

This section outlines the principles for identifying, appraising and optimising city shaping infrastructure to maximise land use and transport benefits.

6.1 Principles

- Respond to the strategic vision by identifying strategic or city shaping infrastructure.

- Understand, and then take advantage of, the impacts that strategic or city shaping infrastructure have on the city’s structure.

6.2 Process

The ITLUP process in relation to strategic or city shaping infrastructure is summarised in Figure 6 and further detailed below.

Figure 6: ITLUP process for strategic or city shaping infrastructure

Source: SGS Economics and Planning Pty Ltd

6.3 Identifying strategic transport infrastructure

Identifying strategic initiatives requires a suitable land use and transportation simulation model that measures shifts in relative accessibility across a city, given the addition or withdrawal of strategic links and/or the spatial reallocation of substantial numbers of jobs through other policy interventions. Only initiatives that can demonstrably and significantly raise or lower the relative accessibility of a particular area of the city would merit strategic designation (Spiller et al., 2012).

Questions to consider when identifying whether infrastructure is strategic include:

- Will the initiative demonstrably and significantly raise accessibility?

- Will the initiative substantially redistribute jobs across the region?

- Will the initiative substantially redirect the property market or increase desirability of a particular area?

- Are there opportunities to strategically shift land uses through land use planning in response to the proposed initiative?

To properly assess if there are realistic (rather than theoretical) opportunities for land use change following an increase in accessibility, the land use context must be closely considered. For example, the Sydney Metro City and South West initiative (see below) is expected to substantially increase accessibility to jobs within the Sydenham to Bankstown corridor. But, hypothetically, if there are too many constraints within the corridor - such as fragmented land ownership or substantial redevelopment having already taken place - then the opportunities for significant change and therefore city shaping may be limited.

The task of answering the above questions is assisted by using quantitative measures such as effective job density[1] and the simpler measure of jobs accessible within 30 minutes. The change in these measures produced by the transport initiative indicates the scale of their impact.

Note that projects that result in a significant shift in mode share rather than land use are not considered strategic. For example, while the Gold Coast light rail is an important transport project for the city and has resulted in an increase in public transport use, it is considered to be structural infrastructure rather than strategic infrastructure because it has not significantly shifted the way land is used.

As there is no precise benchmark or threshold to identify strategic or city shaping infrastructure, the discussion below highlights examples showing the variation in levels of impact, as well as the process involved in measuring the impact.

Box 1: Measuring the impact of strategic infrastructure using effective job density

Measuring the impact of strategic infrastructure requires a calculation of EJD within a small area under a base case scenario. By inputting a travel time matrix and employment at a small area level, the change in EJD brought about by a specific infrastructure and/or land use initiative can be established in the same way the base case EJD is estimated.

Inputs will differ in terms of a changed travel time matrix or employment numbers in response to projected changes or uplifts in employment in different locations across the region and changes in travel times associated with the infrastructure initiative.

6.3.1 Effective job density - CityLink and Western Ring Road in Melbourne

Melbourne's CityLink had a maximum EJD increase of 5.4% (Figure 7), while the Western Ring Road initiative had an EJD change of 1.7% (Figure 8) - suggesting the CityLink initiative has a more significant impact on Melbourne’s structure.

Figure 7: EJD change for CityLink

Source: SGS Economics and Planning Pty Ltd

Figure 8: EJD change for Western Ring Road

Source: SGS Economics and Planning Pty Ltd

6.4 Examples of strategic or city shaping infrastructure

6.4.1 Sydney Metro City and South West (NSW)

The proposed Sydney Metro City and South West infrastructure initiative will extend the Sydney Metro North West from Chatswood to Bankstown with a new metro line between Chatswood and Sydenham and conversion of the existing railway line between Sydenham and Bankstown to metro operations. It is intended to increase the number of trains travelling through the CBD during peak hour. A number of new stations are proposed along the new rail line between Chatswood and Sydenham including a station at Barangaroo and Waterloo (refer to Figure 9).

Figure 9: Sydney Metro City and South West alignment

Source: Transport for NSW, 2015

The Sydney Metro City and South West is expected to substantially increase accessibility from the corridor to employment opportunities concentrated across Sydney CBD. The initiative is considered to be city shaping because of this substantial shift in accessibility for residents within the Sydenham to Bankstown corridor, as well as its impact on the property market and opportunities to strategically shift land uses.

The station at Waterloo is expected not only to increase the proportion of jobs accessible within 30 minutes for existing residents, but also to shape land use near the railway station The NSW Government-owned land (social housing) was marked for redevelopment as a mixed housing estate with the station at Waterloo driving the future redevelopment. This highlights that land use considerations, such as redevelopment opportunities, should be incorporated into the detailed alignment of a transport infrastructure initiative. Similarly, structure planning along the Sydenham to Bankstown section of the corridor has identified opportunities for increasing housing supply and improving amenity.

6.4.2 Crossrail (London, United Kingdom)

Crossrail is currently under construction in London and will link Heathrow Airport, the West End, the City of London and Canary Wharf through an underground tunnel under central and south east London. The initiative is expected to improve access for 750,000 workers who currently commute into London (Crossrail 2015). Figure 10 highlights the projected impact on accessibility to jobs.

Figure 10: Crossrail impact on access to jobs

Source: Crossrail 2011

Crossrail is also expected to impact London’s economic structure, particularly the finance and business services market. Potential new jobs expected as a result of Crossrail are likely to be internationally mobile jobs; that is, if they were to locate elsewhere, they would likely locate in other major global cities such as Paris or Frankfurt rather than other areas of the UK (Meeks et al., 2002). This demonstrates the significant structural shift and city shaping potential of Crossrail.

6.4.3 Mandurah railway line (Western Australia)

Investment in modern heavy rail commuter infrastructure is transforming Perth’s urban structure. The Mandurah railway line opened in 2007. It is a suburban railway line that runs through the south western suburbs of Perth, connecting .Perth with Mandurah via Rockingham. While operating conditions in the new suburban rail system are not always ideal - for example, some train services run down the centre of freeways - the community has flocked to the network. It has influenced more compact forms of satellite development in the northern growth areas of Perth while improving accessibility to the Perth CBD.

More recently, investment in a new southern line linking to Mandurah has established the potential for a string of transit oriented developments that are actively being pursued by the WA Government in line with the vision set out in successive metropolitan strategies.

Figure 11: Mandurah Line - clockwise from left: stops and feeder bus routes; park and ride facilities and new hospital; Murdoch station

Source: McIntosh et al, 2015

6.5 Assessing the impact of strategic transport infrastructure on urban structure

Rigorous assessment is particularly important for strategic/city shaping initiatives. Having demonstrated the city shaping impact of a transport initiative (influencing location decisions of households and firms), practitioners need to measure whether this impact will help or hinder achievement of metropolitan settlement pattern objectives, as set out in spatial vision and/or strategic plan for the city.

One approach is to apply historically observed locational elasticities (the measured sensitivity of employment or population growth at the travel zone[2] level to changes in past levels of relative accessibility). Locational elasticity will be sector-specific. Some industries, particularly high value added sectors like financial and professional services, require and are prepared to pay for, premium accessibility.

6.5.1 Rationale behind the location of different land use activities

Businesses

Well established economic theory[3] indicates that over time, firms will tend to locate closer to areas that deliver the greatest economic benefits to them. These benefits can be in the form of the most efficient land use for the firm. In addition, locating in areas with superior accessibility reduces transaction costs through ease of contact with suppliers and customers, while increasing access to a skilled labour force.

While all firms prefer locations with high levels of accessibility their ability and willingness to pay for locational advantages will differ, as will their aggregate land use demands. Land use demands between industries and the type of workers generally differ based on the functioning of their industries.

Land use demands from service industries are small relative to industries such as manufacturing and wholesale trade, which require large amounts of land. Land rents for service industries can be shared across multiple firms as office towers adopt the relatively cheaper option of expanding vertically rather than requiring large parcels of land. This contributes to the ability of service firms to locate within the confines of a dense area of employment and population such as a CBD, whereas manufacturing and wholesale trade tend to locate further away from dense areas.

Ways to improve business accessibility differ across industries based on their customer and supplier base. Generally, manufacturing firms require quality road infrastructure and tend to locate closer to areas with access to major road networks. Both their suppliers and customers also tend to have a similar accessibility requirements. Efficiencies can be gained for these industries when they locate closer to points of road infrastructure.

In contrast, while service industries require timely access to their suppliers, employees and customers, their ability to access those people differs based on the function of their business models.

Households

Opportunities for access to employment apply in a similar way to households as they do for industries. People, over time, will adjust where they live due to many factors, including access to employment, education, essential services and recreation. However, the literature indicates these choices tend to be constrained due to factors such as family and historical ties to a region or corridor.

For these reasons, many people and families that do relocate tend to move within corridors (or within housing submarkets) rather than across town. When cross-town moves are made, the relative accessibility of the two areas is a key consideration.

6.5.2 Assessment process and techniques

Conventional practice often assumes no change in demographics or industry types between the Base Case and Project Case (without and with the strategic transport investment). However, it is possible to quantify the impacts of such initiatives in relation to specific metropolitan objectives, when households and businesses adjust their location in response to a change in an area’s accessibility. This may include assessing trends such as land consolidation versus urban sprawl, or the level of assistance offered by the government to key metropolitan industry clusters and economic nodes to reinforce agglomeration economies (Spiller et al., 2012).

Modelling impact on housing densities

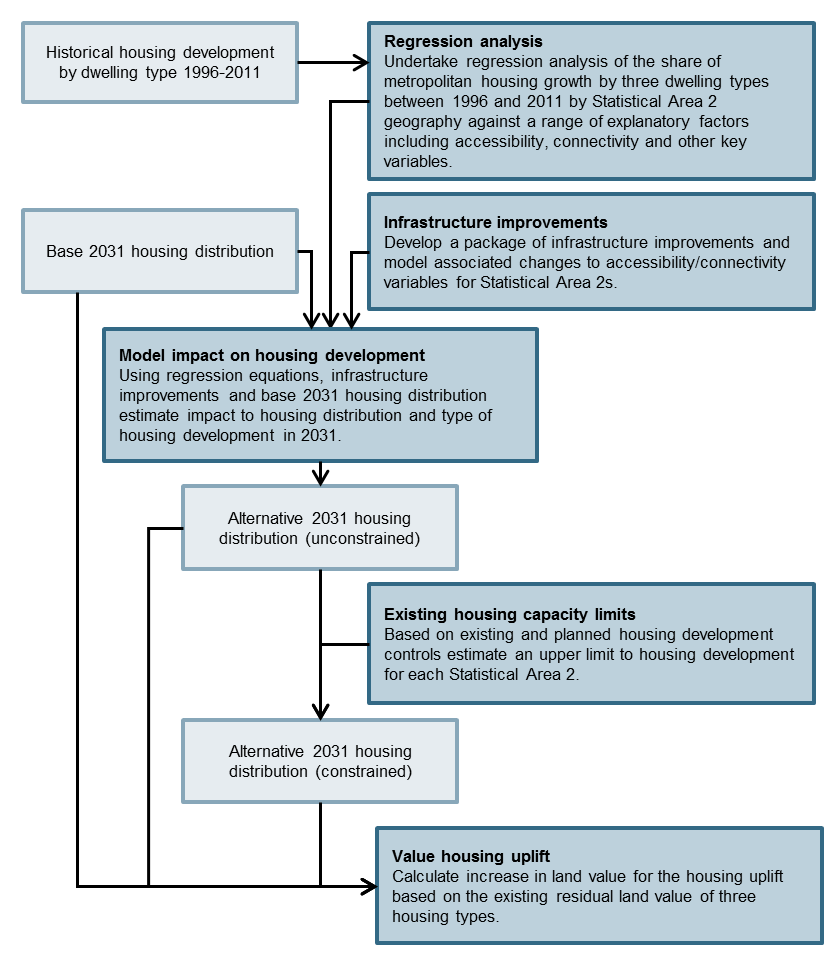

The Commonwealth Treasury published a report by SGS Economics and Planning (2013) prepared for the former National Housing Supply Council that demonstrated methods to model the impact of strategic initiatives on housing densities across metropolitan areas, using Sydney and Melbourne as case studies.

The analysis sought to estimate the extent to which infrastructure investment improves connectivity, as well as the extent to which accessibility influences housing development. The model operated at a metropolitan level given that an increase in supply in one location is likely to impact supply in another.

Figure 12 provides an overview of the approach adopted within the study, the key inputs/outputs and analytical tasks competed as part of the analysis.

First, statistical relationships between housing development and accessibility were developed based on historical data. These outputs were fed into a model that redistributes housing development across the metropolitan area from one area to another and between housing types based on accessibility profiles of locations. This compared the level of EJD under the Base Case with that expected under the Project Case. All other variables were assumed to be constant across both the Base Case and Project Case. If there was no impact to EJD, then the location’s housing development remained as per the Base Case. If EJD increased/decreased, then the amount and mix of housing was adjusted in line with the regression coefficients.

Figure 12: Example of housing analysis process

SGS Economics and Planning Pty Ltd

Impact of infrastructure on housing types in Melbourne

An assumed percentage uplift in relative EJD was applied to the inner, middle and outer rings of Melbourne, based on previous work completed by SGS on major transport infrastructure projects (14% for inner, 7% for middle and 2% for outer rings). These are hypothetical scenarios, devised for analytical purposes only.

Figure 13 shows the Base Case and Project Case growth in the number of dwellings (by detached, semi-detached and apartments) in 2031 for the inner, middle and outer rings of Melbourne using a Melbourne EJD coefficient. Under these scenarios, the number of apartments across Melbourne would increase, especially in the inner and middle rings. The number of semi-detached houses was not expected to change between the Base and Project Cases, and the number of detached houses fell between the Base and Project Cases, especially in the middle ring, which was projected to contain the greatest proportion of dwellings in 2031.

Figure 13: Summary results by ring and dwelling type for Melbourne

Source: SGS Economics and Planning Pty Ltd

These results reflect the strong statistical relationship between accessibility (EJD) and higher density housing development in Melbourne. With an increase in accessibility, there is a strong increase in the number of apartments in a location. This has the impact of reducing the amount of land required on the urban fringe for detached housing.

While major transport investment may generate the potential for housing intensification, the extent of this potential will depend on a range of factors. including the appropriateness of the planning controls affecting the areas in question. It should also be noted that underlying housing development potential may not find expression because of market failures such as fragmented land holdings. Similarly, key brownfield sites for housing construction may be constrained by unknown contamination risk or lack of coordinated asset management among institutional owners.

Land use transport interaction model

A key input to strategic transport models is land use information, with the interaction between transport and land use within those models being increasingly seen as highly important in integrated planning. There is still some uncertainty, however, as to the most appropriate method of implementing land use transport interaction (LUTI) models with reoccurring tension between theoretical preferred options and practical implementation including issues associated with induced demand. Further discussion relating to LUTI modelling and induced demand is contained in ATAP Guidelines Part T1 Travel Demand Modelling.

Investment appraisal tools

Another important aspect of the assessment process is the appraisal of transport initiatives, particularly strategic initiatives.

As highlighted elsewhere in the ATAP Guidelines (see Parts F3 and T2), the key investment appraisal tool is a cost benefit analysis (CBA), which determines whether an initiative’s economic benefits (including reductions in maintenance, operating and external costs) justify the capital costs, especially when the same resources could be deployed to other socially productive uses. In the ATAP Guidelines (see Part F4), the CBA is a key requirement of the comprehensive business case.

CBAs, as applied to major transport investments, cover a range of impacts, primarily user benefits, but also non-user benefits such as emissions, safety and externalities. CBAs are evolving to include less tangible impacts such as neighbourhood disruption and amenity. Important equity issues are not included in CBAs, but are considered separately alongside them.

In addition, agglomeration economies are increasingly being considered in CBAs as a ‘wider economic benefit’ (or WEB). These agglomeration WEBs are productivity gains resulting from economic agents (businesses and households) having better connections to each other so they can better meet one another’s needs and share information (see Part T3 of the ATAP Guidelines for a discussion on WEBs). CBAs are increasingly being applied to active travel, recognising the health and decongestion benefits from increased cycling and walking. (see Table 2).

| Potential benefits generated by a new transport link | Traditional CBA | Traditional CBA + WEBs | Traditional CBA + WEBs + Human Capital Effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reduced business transport costs, enabling expanded production | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Reduced household travel costs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Agglomeration economies improve business to business synergies | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Less transport constraints expand high value added industries in propitious locations, allowing a shift to more productive jobs | ✓✗ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Better labour matching improve labour participation and productivity | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Enriched human capital thanks to expanded formal and tacit learning opportunities | ✓✗ | ✓✗ | ✓ |

| Expanded households choice (consumption, learning, employment) | ✓✗ | ✓ | ✓ |

Source: SGS Economics and Planning

Ideally, CBAs will cover these broad benefits. However, even if analyses identify a broader range of impacts, they still face analytical restrictions that limit their efficacy in the context of strategic initiatives.

For example, CBAs conventionally restrict measured impacts to the first round effects of initiatives. These may be subject to lags, but have a direct cause and effect link with the initiative under appraisal. Indirect and feedback effects are usually excluded from CBAs for two reasons:

- First, if the indirect effects merely reflect passing on of direct impacts throughout the urban economy, then it is correct to exclude them. To do otherwise would lead to double counting of benefits. CBA avoids potential double counting by measuring benefits directly at their sources (as time and cost savings to transport users).

- Secondly, for practical reasons, considering second and subsequent round effects requires complex assessment of the urban economy as many linked decisions and feedback loops come into play with strategic transport infrastructure. This assessment would require the application of dynamic general equilibrium modelling to an urban context, tracking feedback effects and linking them to land use outcomes. While such modelling may enhance understanding of the full impacts of strategic initiatives, the associated modelling costs need to be considered. Extensive data gathering is required and the process is open to challenge as multiple judgements are required throughout the process. Nevertheless, use of such models would allow fully evolved CBAs to be undertaken.

Given the dynamic nature of transport and land use interactions, defining the Base Case land use for CBAs can also be challenging.

An alternative to this fully evolved CBA approach is the iterative application of rapid and detailed CBAs using land use impact scenario analysis. In this approach, scenario analysis is used to investigate the potential major land use impacts of strategic transport initiatives. Testing the effect of different land use impact outcomes on a CBA determines the sensitivity of the CBA results.

Another alternative is to use multi-criteria analysis (MCA) – a more qualitative assessment option. An MCA can be used prior to a CBA, at early stages of options assessment when limited quantitative data is available for even a rapid CBA. An MCA requires specification of criteria on which to rate options and consideration of how each option measures up against each criterion. The criteria can also be weighted to account for their relative importance. Each option’s rating can be compared to other options based on the sum of its performance against the weighted criteria (Prosser et al., 2015). However, an MCA can involve risks of bias, lack of transparency and ease of manipulation to obtain a predetermined result (see discussion in Part F3, Sections 3.2 and 3.3, especially Box 1 of the ATAP Guidelines). Transparent use of MCA, and limiting its use to early comparison of options prior to a CBA, will help mitigate those risks.

Jurisdictional goals, transport system objectives and government policies can be used to formulate the criteria for an MCA. This allows for initiatives or transport corridors to be assessed against the achievement of government policies. Upfront identification of objectives helps avoid bias during the assessment process. This is similar to the Strategic Merit Test, or Objectives Impact Table tools discussed in Part F3 of the ATAP Guidelines.

An MCA is flexible – it can be applied to the identification of high-level strategic transport corridors across a city as well as the comparison of specific routes for a transport initiative. An MCA’s objectives and criteria can be altered and amended during the process if they are considered to be inappropriate or irrelevant (Prosser et al., 2015). Again, this must be done with rigour, scrutiny and transparency to ensure an unbiased assessment.

6.6 Optimising city shaping power

Strong coordination of actions is required to optimise the city shaping power of transport infrastructure. Those actions will differ between brownfield and greenfield areas.

In brownfield areas, the focus will generally need to be on consolidating land uses to unlock potential. SGS Economics and Planning (2013) suggests that the area of influence of key transport investments can be broken down into a number of components (refer to Figure 14) including key redevelopment districts, high and moderate impact areas and a value capture district. An explanation of principles to optimise land use opportunities within these areas is detailed below. This approach may vary for road infrastructure initiatives.

Figure 14: Schematic of impact areas within a transport corridor

Source: SGS Economics and Planning Pty Ltd

In greenfield areas, the focus will likely be on coordinating complementary investments to support the growing population including local infrastructure such as water and sewage and social infrastructure such as hospitals and education facilities. Strong coordination between government and the private sector will optimise city shaping power, particularly the sequencing and staging of infrastructure in relation to land use development. See Section 8 for more details.

6.6.1 Unlocking land use potential

Key redevelopment districts demonstrate greater potential for transport-induced housing intensification. Their potential can be unlocked by commissioning state development corporations[4] to overcome barriers to private sector investment in housing and related regeneration initiatives. These barriers or market failures include land fragmentation, land contamination, local infrastructure gaps and poor coordination between government land holders.

In the wider area of impact, unlocking land use potential may require a stronger, de-politicised planning system that applies subsidiarity to the allocation of plan-making roles across the different levels of governance, and that ensures greater transparency and conceptual clarity in the application of upfront infrastructure development contributions.

The land use potential will vary by type of transport infrastructure. Aviation infrastructure can have a significant impact on existing and proposed land uses due to aircraft noise. The National Airports Safeguarding Framework provides guidance relating to land use planning around airports to maximise aviation and community safety and minimise aircraft noise impacts on communities.

Potential for land value capture

Land value capture districts are the areas that benefit from the transport initiative and could be a candidate for strategies to raise funds for reinvestment in infrastructure by linking to the uplift in land value enjoyed by constituent properties. A range of mechanisms can be used to capture a portion of this land value uplift, including area-wide infrastructure contributions.

6.6.2 Affordable housing

Investment in strategic transport initiatives can effectively expand the supply of land available for housing development, which may place downward pressure on housing prices. Spatially, this affordability benefit is likely to be felt most in outer urban and in less well connected parts of a city, which will have to compete more strenuously on price to attract buyers and tenants.

However, areas enjoying a boost in connectivity and therefore higher housing activity can be expected to maintain a price premium. Community sustainability and local economic functionality such as access to key workers warrant the reservation of some housing for lower and middle income groups in areas of high uplift. This can occur by either or both of:

- Dedicating a proportion of the proceeds from any tax on broad area value uplift to the provision of social housing

- Applying area-wide inclusionary zoning so that all development in the advantaged areas must incorporate a proportion of affordable housing or make cash in lieu contributions so that this obligation might be met elsewhere within the same broad district.

6.6.3 Social impacts

Transport infrastructure can improve access to employment for low socio-economic areas within a city, particularly by increasing the proportion of jobs accessible within 30 minutes. This can occur if the transport initiative specifically improves direct access to an existing employment area or if new employment opportunities are created near lower socioeconomic areas. This occurred in Melbourne when Tullamarine Airport created significant employment opportunities in the north west growth corridor. The impact of a transport infrastructure initiative on lower socio-economic areas can be measured by calculating the uplift in the number of jobs accessible within 30 minutes for particular target regions of the metropolitan area.

Transport infrastructure, through an uplift in the value of land impacted by the increase in accessibility, may price low income earners out of the market. This impact can be considered and addressed by incorporating affordable housing into redevelopment areas.

6.6.4 Indirect effects

Infrastructure initiatives can also have indirect impacts on land use where land is made available for alternate and often higher value uses where an infrastructure initiative shifts land uses. This often includes the shifting of industrial land out of the inner city waterfront to free up land for residential or other higher value uses.

An example of this includes the Western Ring Road in Melbourne (see case study below). Other examples include:

- The Brighton transport hub in Hobart, an inland intermodal hub that allowed for the redevelopment of The Hobart Railyards, a former inner city intermodal terminal

- Barangaroo in Sydney, made possible when port facilities relocated to Port Botany

- The Bowden Clipsal factory redevelopment in Adelaide, made possible when the factory relocated to Gepps Cross.

Case study: The Western Ring Road

The Western Ring Road extends 28 kilometres from the junction of the Princes and West Gate Freeways in Laverton to Sydney Road/Hume Highway in Fawkner. Through this section the Ring Road connects to all of Melbourne’s western and northern highways: the West Gate, Princes, Western, Calder, Tullamarine and Hume freeways (see Figure 15).

Figure 15: Western Ring Road Connectivity

Source: SGS Economics & Planning Pty Ltd

The Western Ring Road was anticipated to deliver major economic benefits to Victoria by linking up the national freight corridors with the Port of Melbourne and Melbourne Airport (VicRoads, 1994). As it connects the individual freeways that service Melbourne’s sea and airports, the movement of freight is one of the road’s primary functions. It also relieves freight traffic from Sydney Road, Pascoe Vale Road and Geelong Road.

The heavy freight use has spurred industrial growth along the Ring Road, resulting in a redistribution of Melbourne’s industry. In the late 1980s, a decision was made not to rebuild the wharves that now house the Docklands development, which subsequently allowed for the area’s regeneration.

The road’s construction in the 1990s allowed the existing industries in the Docklands to relocate to cheap industrial land with good access to the port. This freed up suburbs like the Docklands, Richmond and Brunswick for residential and commercial redevelopment.

[1] Effective Job Density is a statistical index of agglomeration in economic activity; it comprises the number of jobs in a locality plus all the jobs situated elsewhere that can be reached from that locality, divided by the travel time involved in reaching them

[2] A travel zone (TZ) is a geographic unit of data collection, transport modelling and analysis. TZs allow for detailed spatial analysis as they are smaller than Statistical Local Areas (SLA), but generally larger than an Australian Bureau of Statistics Collection District (CD) or Mesh Block (MB).

[3] Location theory has developed from ideas introduced by Johann Heinrich von Thünen in 1826.

[4] Acknowledging that the involvement of state development corporations are not the only model for redevelopment.