7. Structural and local infrastructure

Structural and local infrastructure sits at the district, corridor, suburb and neighbourhood level to support and respond to strategic or city shaping infrastructure. Structural and local infrastructure is generally planned using the cluster and connect model.

As discussed in Chapter 1, the cluster and connect model reflects the more traditional approach to ITLUP. There is significant published guidance on the cluster and connect aspects of transport and land use planning integration, including the comprehensive, and still largely relevant, Austroads publication Cities for Tomorrow (Westerman, 1998).

Many jurisdictions have issued guidelines that address various aspects of this approach, such as the NSW Long Term Transport Master Plan (Transport for NSW 2012) which describes a four step process of ITLUP:

- Step 1 - integrating transport with land use planning

- Step 2 - identifying corridors of demand

- Step 3 - defining the performance required from the transport network

- Step 4 - moving towards a connected and integrated system.

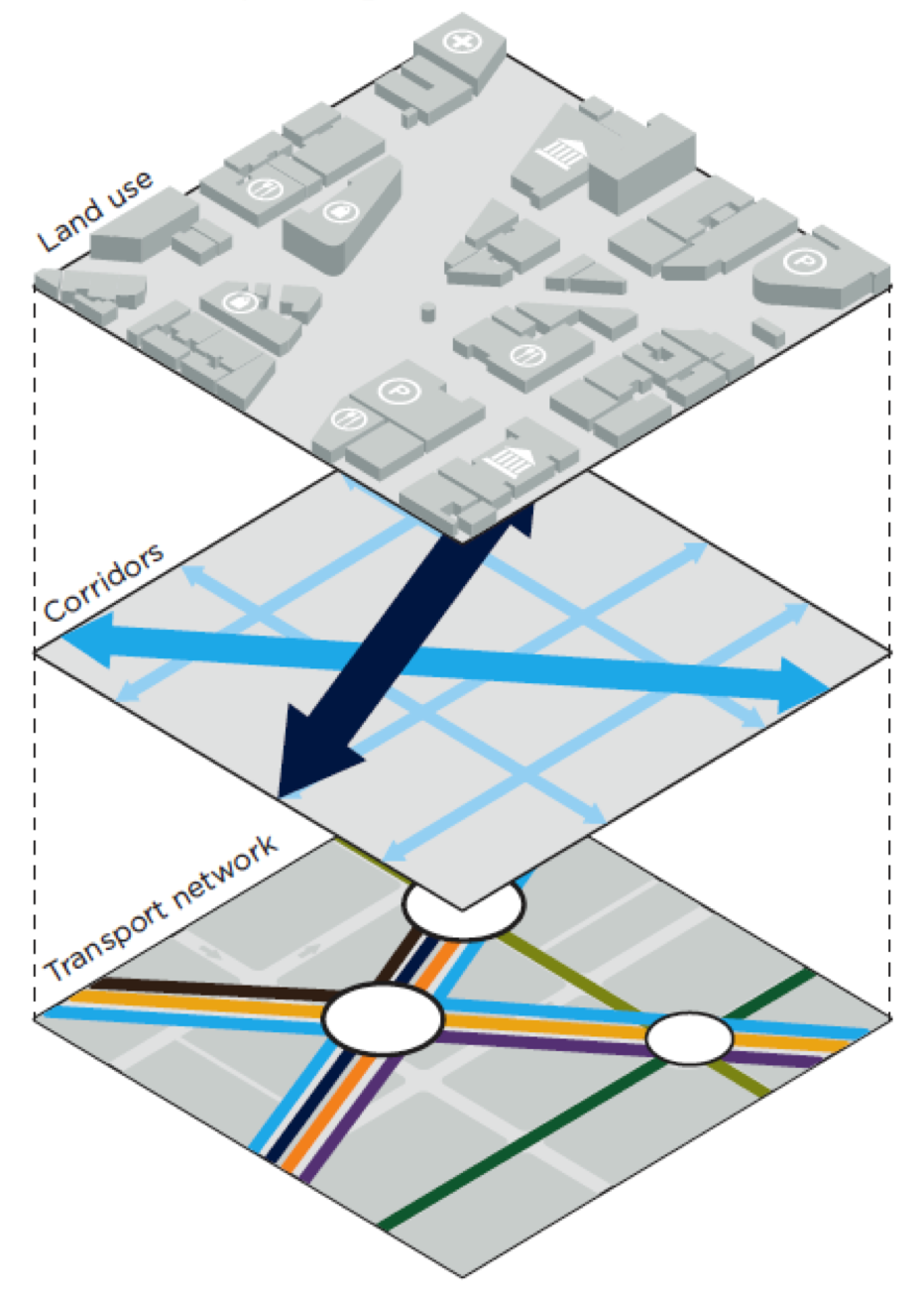

Figure 16: Cluster and connect model: relationship between land use, corridors and network planning

Source: Transport for NSW

As noted in Chapter 1, the cluster and connect approach generally has a strong place-making focus at the neighbourhood level. This is achieved by:

- Consolidating community facilities around public transport or introducing public transport such as light rail[1] to improve local connectivity, calm traffic and promote local development

- Introducing complementary road network policies to keep longer distance traffic on the state and national road network.

This section provides a best-practice approach to the cluster and connect model for application at the corridor, district and local levels. The specific chosen approach will vary within the context of each state or territory, local area and initiative.

7.1 Principles

Cities for Tomorrow (Westerman, 1998) provides an extensive guidance regarding the cluster and connect process and despite having a focus on road infrastructure, the principles and process can be applied to the ITLUP for structural and local transport infrastructure.

State and local governments generally produce guidance in the form of key principles, objectives and frameworks. For example, A Plan for Growing Sydney, the metropolitan plan for Greater Sydney, identifies an action to deliver guidelines for a healthy built environment. Plan Melbourne, the metropolitan plan for Greater Melbourne, promotes the concept of a 20 minute city with the objective that everyday services and jobs will be accessible to residents in a short commute of 20 minutes.

However, the key principles can be constrained because they have only an initiative-specific basis. In contrast, the principles identified below provide a broader guide for fully integrated ITLUP.

7.1.1 District and corridor level

According to Westerman (1998), corridors are defined as transport routes and their associated environments. Planning at a district[2] and corridor level should involve:

- Planning, designing, developing and managing transport infrastructure and its environments as integrated facilities, with provision for at least one transport mode

- Recognising the relationship between the corridor and the adjoining communities, land uses, built form, amenity and environment

- Planning for integration of development controls and traffic management

- Considering the impact of traffic on the safety of pedestrians and cyclists, parking, local businesses and activities, and environmental assets.

7.1.2 Suburb and neighbourhood level

ITLUP at the suburb and neighbourhood level should address issues such as:

- Local urban form with opportunities for more sustainable development

- Integration between local land use and transport to maximise accessibility

- Planning for choice in transport mode

- Ensuring access to public transport

- Precincts for environmental protection and enhancement

- Pedestrian-friendly and safe environments, and centres containing mutually supporting activities

- Transport corridors and facilities that enhance, rather than detract from, the local environment (Westerman, 1998).

7.2 Process

As discussed in Chapter 1, the integrated cluster and connect planning process for transport corridors should align with the strategic vision for the region. Cities for Tomorrow (Westerman, 1998) identifies the development of urban structure and form as core issues of integrated planning. It focuses on the need to integrate land use, transport, the environment, economic and financial resources, the private and public sector and different levels of government. It identifies eight stages to achieve integrated cluster and connect planning at the corridor and local level. This process is summarised in Table 3.

| Stage | Overview |

|---|---|

| Set objectives | This stage encourages and facilitates approaches that contribute to a region’s development. These should be comprehensive, specific, achievable and measurable and link to the metropolitan, subregional or local vision for the area. The objectives should reflect integrated outcomes. Long-term and short-term objectives should be clearly identified. Agreement will need to be sought with the appropriate stakeholders. |

| Problem definition | This stage recognises that there is an issue or problem that needs to be addressed through an integrated approach. This includes developing an understanding of the context and what is needed to address the problem. The main outcome of this stage should be a shared commitment to proceed with a study, strategy or plan and securing funding to undertake this process. |

| Institutional setting | This stage clarifies which public agencies are involved in the process, their roles and contributions and who has primary responsibility. An appropriate model should be developed and high-level commitment from both the public and private sectors should be sought. |

| Determine the desired outcomes | This stage determines the desired outcomes and setting priorities. This should account for the roles and responsibilities of stakeholders, relationships with existing strategies and actions, and options for different approaches. |

| Define the scope | This stage identifies the area of application, which may include a region, metropolitan area, local area, a combination of adjoining local areas or the relationship between metropolitan and local areas. Alternatively, this could include a particular land use, transport or environmental interaction, such as the relationship between activity and accessibility. At a district level, the focus will be on the structuring and adaption of urban regions, providing for growth and change while moving towards more sustainable, efficient and equitable urban areas. This may relate to land use and infrastructure planning, travel demand management, managing accessibility and activity and protecting the district environment. At a local level, issues may involve establishing a local land use transport system with a closer fit between housing, local land use and the transport system with other housing, local employment and services. Key issues relate to making activity centres more pedestrian friendly with a range of facilities and services. |

| Select and develop a package of tools/options | This stage explores the range of tools/options available to determine those that are relevant. The outcome will involve selecting and developing a package of tools/options that will contribute to greater integration. Examples of these tools are detailed in the following section. |

| Determine the required actions | This stage ensures agreement on the final outputs and required actions. Targets should be practical, achievable and measurable. Outputs may include a strategy or policy, development plans and designs, the implementation of integrated programs, or specific initiatives (investment and non-investment). |

| Monitoring and feedback | This stage ensures actions are producing the desired outputs and outcomes and, if circumstances change, that the plan or initiative can adapt. |

Source: adapted from Westerman, 1998, including ordering stages to align with ATAP

This approach is not definitive and is considered to be flexible depending on the context.

7.3 Other relevant guidelines

The following guidelines are also considered useful references for the cluster and connect model.

- Principles for Strategic Planning

Produced by Austroads (1998)

Principles for Strategic Planning assists professionals, particularly those working in land use and transport, to conduct sound, methodical and effective strategic planning. It explains the principles of strategic planning and provides a model of the strategic planning process. It conveys the concepts involved in clear strategic thinking (concepts that can be applied to issues that arise day-to-day in any busy office), as well as the steps involved in undertaking formal strategic planning exercises.

While not specifically tailored to ITLUP, the document provides principles and a process to guide the wider strategic planning process and reflects some of the elements of the best practice guidance discussed above. - Improving Transport Choice – Guidelines for Planning and Development Policy

Produced by NSW Department of Urban Affairs and Planning (2001)

These guidelines are part of the Integrating Land Use and Transport policy package. They provide advice on how local councils, the development industry, state agencies, other transport providers and the community can better integrate land use and transport planning and development and provide transport choice and manage travel demand to improve the environment, accessibility and liveability. They focus on creating areas, land uses and development designs that support more sustainable transport outcomes. In particular they provide principles, initiatives and best practice examples for locating land uses and designing development that encourages viable and more sustainable transport modes than the private car, such as public transport, walking and cycling. - The Right Place for Business and Services – Planning Policy

Produced by NSW Department of Urban Affairs and Planning (2001) - Integrated Transport Planning Framework for Queensland

Produced by Queensland Government (2003) - Planning Guidelines for Walking and Cycling

Produced by NSW Department of Infrastructure, Planning and Natural Resources (2004)

The Planning guidelines for walking and cycling assist land use planners and related professionals to better consider walking and cycling in their work and consequently create more opportunities for people to live in places with easy walking and cycling access to urban services and public transport. - Developing a Local Cycle Strategy and Local Cycle Network Plan

Produced by Queensland Transport (2006)

This series of notes assists planners and engineers to provide for cycling in their local area. - Precinct Structure Planning Guidelines

Produced by Victorian Growth Areas Authority (2009)

Of most relevance are the Guidelines Notes – Our Roads: Connecting People. This document provides guidance and direction about the road network hierarchy and road cross sections in Melbourne’s growth areas. It complements Growth Area Framework Plans, which identify basic arterial road networks in growth areas. - Guidelines for Preparation of Integrated Transport Plans

Produced by Western Australian Planning Commission (2012)

The guidelines provide guidance to local governments to develop and implement integrated transport plans and enable an effective approach to local transport planning and transport infrastructure, maintenance and service delivery (where local government is a core player).

While the focus is on preparing plans rather than guiding initiatives, these guidelines remain a relevant source for ITLUP. - Hume Integrated Land Use and Transport Strategy

Produced by Hume City Council (2013)

The Hume Integrated Transport and Land Use Strategy covers public transport, walking, cycling, traffic and parking management initiatives to improve transport options for Hume residents. It aims to create more accessible, liveable and sustainable communities, giving residents full access to jobs, education, and shopping and community facilities by expanding the range of transport choices and modes.

This example of a tailored local council strategy may be useful for other local governments. - Regional Integrated Transport Strategy 2014-2016

Produced by Eastern Metropolitan Regional Council

The Regional Integrated Transport Strategy 2014-2016 sets out the strategic plan for developing an integrated transport network in Perth’s Eastern Region. The strategy focuses on integrated planning, TravelSmart, public and active transport.

7.4 Tools for implementation

Cities for Tomorrow outlines a range of tools for implementation of ITLUP which vary based on whether the initiative is district, corridor or local (see Table 4).

| District | Corridor | Local |

|---|---|---|

| Urban structure and form | Corridor categorisation | Activity/accessibility zoning |

| Urban density | Planning new Type I corridors | Transit-friendly land use |

| The right activity in the right location | Planning new Type II corridors | Increasing choices in transport |

| A hierarchy of multi-purpose centres | Adapting Type I corridors | Increasing choices in land use |

| Key district and transit centres | Adapting Type II corridors | Cycle networks and land use |

| Public transport and land use | Access to roads | Pedestrians and land use |

| Freight movement and land use | The right transport task on the right mode | Parking standards and management |

| Road systems and land use | Congestion management | Corridors and precincts |

| Integrated development areas | Transport pricing and tolls | Centres as precincts |

| Integrating investment | Intelligent Transport Systems | Residential precincts |

| Air quality and traffic noise | Reducing noise exposure through design | Traffic calming |

| District parking policies | Maintaining community cohesion | Safety |

| Travel demand management | Visual enhancement | Visibility |

| Commuter planning | Urban corridor management | Incentives and contributions |

| Travel blending | Rural corridor management | Performance-based development control |

| Keeping options open | Roadside services |

Source: Adapted from Westerman, 1998

Type I corridors are defined as primary transport routes and their environments, where the through transport function is dominant and adjoining areas are planned, designed and managed to reduce or eliminate friction and impact.

Type II corridors are defined as secondary transport routes and their environments, where both the transport function and frontage function are important.

Additionally, jurisdictions often classify transport corridors based on a functional hierarchy. A functional hierarchy identifies which transport corridors are important for different modes of transport (such as public transport, freight and so on). Similar corridors and locations can be identified for public transport, freight, pedestrians and commuter traffic. Overlapping functions do not mean that one function is more important than another, but rather that the transport corridor needs to cater for more than one function (South Australian Department of Planning, Transport and Infrastructure, 2013).

The hierarchy adopted by the South Australian Department of Planning, Transport and Infrastructure (2013) comprises:

- Public transport corridors

- Cycling routes

- Pedestrian access areas

- Major traffic routes

- Freight routes

- Peak hour routes

- Tourist routes

- Key outback routes.

For further detail refer to A Functional Hierarchy for South Australia’s Land Transport Network (South Australian Department of Planning, Transport and Infrastructure, 2013)

For further detail on the implementation tools identified above refer to Cities for Tomorrow (Westerman, 1998).

7.4.1 The right activity in the right location

The location of activities should be based on their mobility needs and the accessibility provided by the transport infrastructure. Private investment should be linked to public investment in transport infrastructure to maximise the benefits of the investment.

This can be achieved by establishing accessibility criteria for different types of locations, setting targets for public transport use and preparing development and implementation plans for existing locations. District planning instruments and local strategies can also be adopted to implement the right activity in the right location.

Figure 17 illustrates the concept of establishing criteria for three different locations and highlights the need to understand the suitability of particular land uses for locations with high accessibility by public transport or by car. For example, high density residential uses are suitable for locations with high accessibility by public transport (for example location B) and industrial uses, such as freight, are suitable for locations with road access (for example location C).

Figure 17: Land use activity by location and accessibility type

Source: Westerman, 1998

7.4.2 Integrated development areas

Cities for Tomorrow provides guidance on achieving integrated outcomes for defined development areas including both growth and established areas. This implementation tool is focused on co-ordinating development and infrastructure provision to provide a framework and context for integrated programming and budgeting. This process includes:

- Identifying development areas

- Analysing opportunities and constraints

- Addressing measures needed to overcome constraints

- Establishing management structures

- Preparing development plans

- Preparing phasing plans

- Preparing funding plans

- Developing integrated budgets

For further detail refer to R-9 Integrated development areas in Cities for Tomorrow (Westerman, 1998).

7.5 Case studies

A number of case studies across Australia demonstrate best practice applications of cluster and connect planning.

7.5.1 Sydney CBD and South East light rail (NSW)

The NSW Government announced its commitment to the CBD and South East Light Rail in 2012. The light rail line will connect Circular Quay with Randwick via Town Hall and Central railway stations. George Street, between Hunter and Bathurst Streets, will become pedestrianised as part of the initiative. The City of Sydney is working with the NSW Government to integrate the light rail initiative with surrounding land uses, particularly by improving the public domain for people who live, shop, visit and work in the City of Sydney. The City has released a concept design that sets out the principles including creating a safe shared environment for light rail and pedestrians and minimising the visual impact of light rail infrastructure (see Figure 18).

Figure 18: Principles for light rail as part of the concept plan

Source: City of Sydney 2015

The concept plan is supported by the George Street 2020: A Public Domain Activation Strategy which provides landowners and tenants with a vision for how George Street will become a pedestrian boulevard with light rail running through it and how future developments can make the most of this vision (City of Sydney, 2015). This highlights a coordinated approach between state and local government in terms of ITLUP.

7.5.2 Gold Coast light rail (Qld)

The 13-kilometre Gold Coast Light Rail contains 16 stations between Gold Coast University Hospital and Broadbeach. It was delivered by the Queensland Government and City of Gold Coast. The City’s Gold Coast Rapid Transit Corridor Study provided recommendations for the 2,000 hectares of land surrounding the light rail line.

The study aligns the City’s vision towards a bold future that can sustain growth and economic development while retaining a lifestyle that is uniquely Gold Coast. This focuses on providing better buildings, better streets and better places (City of Gold Coast 2011). The urban design framework developed through the study is detailed in Figure 19.

The urban design framework incorporates the following elements:

- Progress the concept of the network city by reinforcing the Gold Coast’s traditional beachside villages into a polycentric city form, with the greatest development intensity and heights at the key activity centres of Southport, Surfers Paradise, and Broadbeach

- Establish major east-west movement corridors as future conduits for rapid public and active transport modes that preserve road capacity and support transit oriented development outcomes

- Recognise, preserve and enhance character areas through improved public transport connections and street environments

- Target investment and support within key clusters of economic growth to diversify the Gold Coast’s economic base

- Investigate appropriate locations for affordable infill residential development to support housing diversity and intensification, boosting housing affordability for key workers and a range of household types

- Create new local community quarters within the coastal strip supported by open space and community facilities to attract permanent residents and families back to urban spine with an emphasis on areas adjoining the cores of Southport, Surfers Paradise and Broadbeach

- Advance an integrated mesh of pedestrian and cycle links connecting across the Nerang River and canal networks to integrate communities and centres

- Create ten great streets or green spines by giving priority to improving the environmental and visual quality of the key movement corridors through the introduction of significant street tree planting and pedestrian facilities.

Figure 19: Gold Coast Rapid Transit Corridor Urban Design Framework

Source: City of Gold Coast, 2011

[1] Light rail has the ability to calm traffic more so than buses because of the priority given to light rail over cars on the road.

[2] The district level is considered to be at a smaller scale than the metropolitan level, but at a greater scale than a local government area (LGA). In some jurisdictions, this is referred to as the subregional level.