1. Introduction

1.1 What are travel behaviour change projects?

This document has been prepared in conjunction with NGTSM Volume 4 Part 2 Urban Transport to provide additional guidance on the assessment of travel behaviour change (TBhC) initiatives.

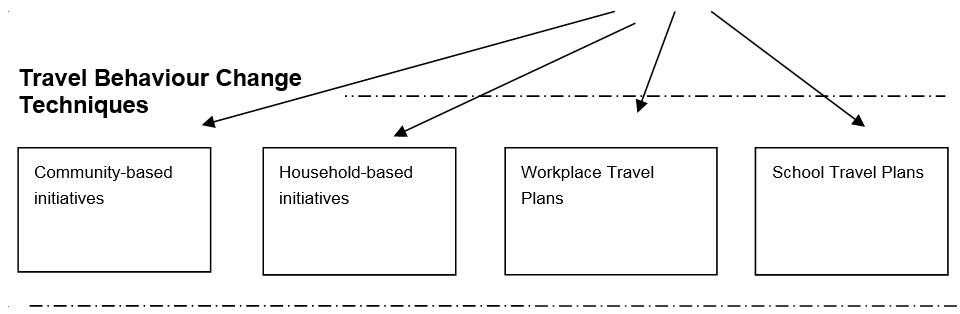

TBhC initiatives and programs are a sub-set of travel demand management measures. Through the use of education, information, and marketing-based approaches they aim to encourage voluntary changes in 'personal' or 'private' travel behaviour to reduce the need to travel, reduce dependence on private cars and increase physical activity. TBhC initiatives may be targeted at the travel patterns and behaviour of the community at large or at individuals within households, workplaces or schools and universities. Table 1 illustrates the relationship between travel behaviour change and other travel demand management measures.

| Travel Demand Management | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strategies | Land use | Network for all users | Travel behaviour change | Pricing/taxes |

| Definition | Shaping community development | Moving people and goods | Voluntary mode shift | Road pricing options User charges / taxes |

| Examples | District plan changes Zoning |

Traffic calming High occupancy vehicle lanes PT services |

Travel planning Personalised marketing Ride share |

Tolls Electronic road pricing Parking supply management |

In Australia TBhC projects have been implemented under various names including Travel Smart, Living Smart, travel blending and others.

TBhC initiatives are often implemented as packages of complementary measures designed to achieve the overall objectives identified in the second paragraph above. Such packages may include small scale infrastructure projects and enhancements. For example, a school travel plan might include upgrading of pedestrian crossings, while a workplace travel plan might include the provision of bicycle lockers.

1.2 Why are separate guidelines needed for TBhC?

The United Kingdom Department for Transport (DfT) makes a useful distinction between:

- 'Hard' measures, defined as measures that have a direct impact on travellers’ generalised cost, whether financial cost, time or other quality factors that are normally valued and included as components of generalised cost

- 'Soft' measures, defined as measures that affect behaviour without affecting travellers’ cost - instead changing travellers’ responses to cost.

Most economic analysis guidelines are focussed on assessing 'hard' measures that change the generalised cost of existing users. Additional guidelines are required for TBhC projects because they mostly comprise 'soft' measures and usually do not change the actual service level, quality or price (and hence generalised cost) of any mode.

Benefit unit values (parameter values) and demand elasticity values for 'hard' measures are provided in the relevant parts of the ATAP Guidelines for public transport and active transport and such measures can generally be assessed using this guidance. However, these other parts of the Guidelines do not contain advice on the responsiveness of demand to TBhC 'soft' measures or on valuing the benefits of such measures. This Part of the Guidelines is intended to fill that gap.

The purpose of many 'hard' measures is also to change travel behaviour - for example, by the provision of physical alternatives or rearrangements (such as infrastructure or revamped public transport services), regulation and enforcement or financial and economic stimulation (such as rewards, fines, taxes, subsidies and pricing policies) that usually leave the individual with little or no choice about how they behave. The distinction between 'hard' measures and travel behaviour change, in terms of how they change behaviour, is the means used to achieve change. TBhC measures tend to approach demand management by supporting and encouraging a change of attitude and behaviour, and are generally non-coercive or voluntary in nature.

Some measures that are traditionally referred to as 'soft', such as real time passenger information systems, bus quality improvements and so on, provide benefits that can be valued and included as components of generalised cost. These should be considered as 'hard' measures and do not require this TBhC guidance.

Separate additional guidance on the assessment of TBhC initiatives is also provided due to the following characteristics of such projects:

- They often comprise a package of several relatively small scale measures.

- With other existing project appraisal procedures, the required level of appraisal effort is disproportionate to the scale of many TBhC projects.

- TBhC projects result in small impacts to a large number of people and the impact tends to be different for each participant, whereas with typical transport projects most users tend to be attributed the same benefit.

- Evidence on the effects of TBhC initiatives and the durability of changes shows significant variations and is still evolving.

- Benefits to travel behaviour changers sometimes appear to be negative when estimated in accordance with standard assessment guidelines and hence require a different valuation approach.

Developing the material contained in this Part through the collaborative national ATAP Guidelines process allows it to act as a standard to promote consistency across Australia in the application of cost–benefit analysis (CBA) to travel behaviour change projects.

1.3 When should these guidelines be used?

These guidelines may be applied when assessing TBhC initiatives involving 'soft' measures and when assessing TBhC packages that include such measures and small scale complementary infrastructure enhancements. Such initiatives and packages are likely to be characterised by changes in travel behaviour and mode changing to public transport and active transport modes that occurs in the absence of any significant benefits to the existing users of these modes.

The following are examples of types of TBhC measures that may be assessed using these guidelines:

-

Community- or household-based initiatives to support efficient travel decisions

- Personalised trip analysis and advice (travel blending, trip chaining, forward planning)

- Pre-trip information about options and conditions for specific trips

- 'Living neighbourhoods'

- Ride share matching service

- Education, information and training

-

Community- or household-based initiatives to encourage reductions in the use of cars

- Marketing of PT / walking / cycling

- Improve image of PT and other environmentally friendly modes

- Advertising and education on travel choices, impacts and costs

- Counter fear of personal insecurity using other environmentally friendly modes

- Marketing of travel choices (such as personalised marketing)

- Education, information and training

- Car clubs / car sharing

-

School travel

- Education and training (such as TravelSmart, cycle training, street crossing behaviour)

- Travel plans

- Establish non-motorised alternatives (walking school buses, cycle trains)

-

Workplace trip reduction

- Workplace parking management / provision

- Company van pools / ride share

- Voluntary trip reduction

- Flexible work hours

- Guaranteed ride home programmes

- Workplace car sharing

-

Substitutes for travel (may be done through workplaces or at a community level)

- Tele-working

- Tele-conferencing

- Tele-shopping / home shopping

- E-commerce

-

Financial inducements to potential users of alternative modes

- Discounts for walking shoes or cycling gear

- Free cycle maintenance

- Discounted public transport tickets

- Free ticket to try public transport.

Workplace travel plans and school travel plans are commonly made up of a package of TBhC measures. 'Personalised marketing' and 'travel blending' projects are also commonly delivered as packages rather than single measures. The elements of such a package may draw upon several of the above measures, as well as possibly including small scale infrastructure and service changes.

These guidelines should not be used to assess projects that involve significant improvements to public transport infrastructure or services, or improvements to cycling and walking infrastructure that can be analysed as 'hard' measures. Such projects should be assessed in accordance with the public transport or active transport guidance as appropriate. Where such projects are being undertaken as part of packages with TBhC measures, only the 'soft' measures should be assessed with these guidelines.

It is difficult to provide a precise threshold for when infrastructure or service enhancements are small scale and can be assessed as part of TBhC packages and when they should be assessed separately. Analysts should make a reasonable judgement in borderline cases. TBhC procedures do not attribute benefits to 'existing' or 'current' public transport or active transport users (those who do not change mode), so where components of a package will provide substantial benefits to existing users it will be more appropriate to analyse these separately from the TBhC package.

In summary, TBhC measures that may be assessed using these guidelines include:

- Household-based initiatives (such as personalised marketing, travel blending or living neighbourhoods)

- Community-based initiatives (such as travel awareness campaigns or ride share initiatives)

- School travel initiatives

- Workplace-based initiatives

- Substitutes for travel (such as teleworking).

Workplaces include commercial business operations, government offices and agencies, community organisations, hospitals, tertiary educational institutions and others.

As noted in Section 1.2, the required level of appraisal effort if a full CBA approach is adopted is disproportionate to the scale of many TBhC initiatives. The economic analysis procedure outlined in Section 5 and illustrated in the worked example is intended to provide a simplified approach that is appropriate for most TBhC initiatives, including smaller scale projects. Economic appraisal may not be justified for very small TBhC initiatives where even the small cost of a simplified CBA is high relative to the cost of the proposed measure.

These guidelines are primarily concerned with the ex-ante economic appraisal of TBhC initiatives. However, guidance on ex-post monitoring and evaluation aspects is also provided in Section 6.

1.4 Background

This Part of he ATAP Guidelines draw on developments and experience over the last 15 years in Australia, the United Kingdom and New Zealand. The economic analysis procedures described in this Part are based on procedures that were developed for Transfund New Zealand (predecessor of the New Zealand Transport Agency) in 2004 (Maunsell et al, 2004a, Maunsell et al, 2004b and Maunsell et al, 2004c) and the Victorian Department of Transport in 2006 (Maunsell, 2006). The New Zealand project included an extensive and thorough review of Australian TBhC projects and project appraisals, as well as TBhC related reports and papers that had been completed up to that time

The procedures have been adapted and updated so that they are aligned with the public transport and active transport guidance provided in the ATAP Guidelines and reflect knowledge gained from more recent monitoring and evaluation of travel behaviour change projects in Australia.

Another useful reference in the development of these guidelines has been the UK Department for Transport’s new Transport Analysis Guidance – Modelling Smarter Choices (DfT, 2014).