Appendix B Private sector considerations

Rationales for government support

As noted in section 5, government may decide to provide financial support to private sector initiatives. Such initiatives might pass the SMT and the CBA but fail the financial appraisal, or fail all of these tests.

If the government wants the initiative to proceed for other reasons, it will need to contribute at least the minimum amount necessary for the commercial operator to receive an acceptable return on the investment. Potential forms of support include a one-off capital contribution, tax concessions, contributions of assets and subsidies.

Where a government contributes financially to such an initiative, robust financial and economic (cost–benefit) appraisals are required. Governments accept the need for commercial investors to make a fair and reasonable return on funds, commensurate with the level of risk. However, they do not support investors making excessive returns at the expense of taxpayers or the paying users of transport infrastructure.

There are several reasons why a government may wish to support an initiative that is not financially viable. They include the existence of externalities, distortionary effects of taxation, the impact of consumers’ surplus and/or the cost of meeting government objectives.

B.1.1 Externalities

The inclusion of non-priced impacts such as externalities in a CBA is one reason why an initiative might pass a CBA test, but fail a financial test. For example, if a rail initiative results in a transfer of freight from road to rail, there may be a net saving in externality costs. However, this net saving would typically not accrue to the rail operator, and hence would be excluded from the operator’s financial appraisal.

B.1.2 Taxation

Taxation makes it more difficult for an initiative to pass a financial appraisal compared with a CBA. Financial analysis takes account of the effects of corporate income tax, while taxes from non-labour inputs are deducted from prices in a CBA.

B.1.3 Consumers' surplus

CBAs include gains in consumers’ surplus, which can make a significant difference where an initiative involves a new transport service or generates new demand. The effect can be particularly pronounced where there is lumpiness in investment. With a downward-sloping demand curve, the larger the initiative, the lower the price that must be charged to ensure that capacity is fully used.

For example, in the case of a new railway line, the smallest scale of investment is the cheapest possible track. If the price that ensures near-full utilisation of the line is too low to cover capital costs, it is still possible that the value to users is greater than the total cost of providing the service. This is because the value to users in a CBA is estimated on the basis of willingness to pay, which exceeds the amount actually paid (the difference being called consumers’ surplus).

Railway operators may capture part of the consumers’ surplus by using market power to set different prices for different tasks and customers (price discrimination). However, in most cases, competition from other modes severely limits the market power of railways. Another means is to purchase land close to proposed stations or terminals to capture increases in land values resulting from the railway initiative.

B.1.4 Costs to meet a government objective

Government contributions to private sector initiatives may be justified where the government, through legislation or negotiation, requires the private investors to modify initiatives to meet government objectives. Without a government contribution, the cost is borne by investors or users.

B.2 Unsolicited private sector proposals

Private sector proposals that are unsolicited[1] should go through an initial government review process. Such a process may be applied when a private sector proponent is seeking government funds to build and/or operate infrastructure or when government approval is required for an initiative that will be self-funded on a commercial basis (e.g. a tollway).

An open environment for private sector and public private partnership (PPP) proposals carries potential risks that should be mitigated through a structured process. Some of the questions to address are:

- What guidelines should apply to the submission of an unsolicited proposal?

- Should there be pre-qualification for the submission of proposals?

- How should the intellectual property be managed?

- What process should be followed for unsolicited proposals compared to a PPP expression of interest or request for tender process?

- What probity framework needs to be in place to ensure transparency and ethical conduct?

These are complex questions that need to be addressed before an effective policy and procedural framework for unsolicited private sector proposals can be implemented. They involve examination of the entities that propose to submit proposals and assessment of any subsequent proposals.

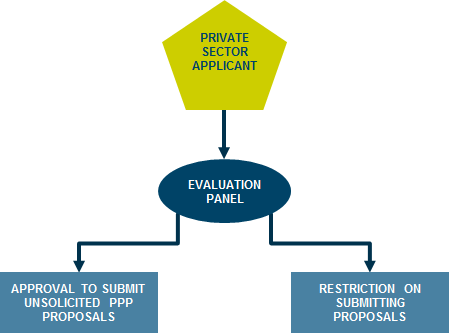

A possible approval process for private sector applicants is illustrated in Figure B.2.1. Under this process, an entity would submit a pre-qualification application to an evaluation panel. Pre-qualification approval would enable the applicant to become a registered entity for the purpose of submitting unsolicited proposals. Restriction would have the broad impact of disqualifying the applicant from involvement with the supply or management of transport infrastructure for a period of time.

Figure 1: Possible approval process for private sector applicants

The evaluation panel would need a set of criteria on which to base evaluation of the applicants. Suggested evaluation criteria are:

- History of ethical conduct with government

- Understanding and accepting best practice in partnering with government

- Track record in delivering transport infrastructure

- Demonstrated capacity for innovation

- Commercial ability to contract

- Attractiveness of relationship plan and approach to unsolicited proposals.

It is likely that many proposals would be submitted by consortia rather than individual proponents. The pre-qualification rule would apply to consortia in the following way:

- The key (largest) equity participant requires pre-qualification.

- A majority of participants, by equity, require pre-qualification.

- All equity participants with an equity participation of 25 per cent or more require pre-qualification.

Table B.2.1 illustrates application of these conditions.

It should be noted that jurisdictions may also have guidance material for assessing unsolicited proposals.

| Consortium | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30% | 30% | |||||||

| Pre-qualified | 30% | 40% | 60% | 75% | 50% | 60% | 40% | 30% |

| Not pre-qualified | 40% | 30% | 40% | 25% | 50% | 20% | 20% | 20% |

| 30% | 20% | 20% | 20% | |||||

| 20% | ||||||||

| 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | |

| Acceptable | No | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| Reason | largest equity participant not qualified | equity majority | >25% | OK | no majority | OK | equity majority | OK |

[1] A solicited proposal is a private sector response to an invitation from government. In contrast, an unsolicited proposal originates within the private sector without any specific invitation from government.